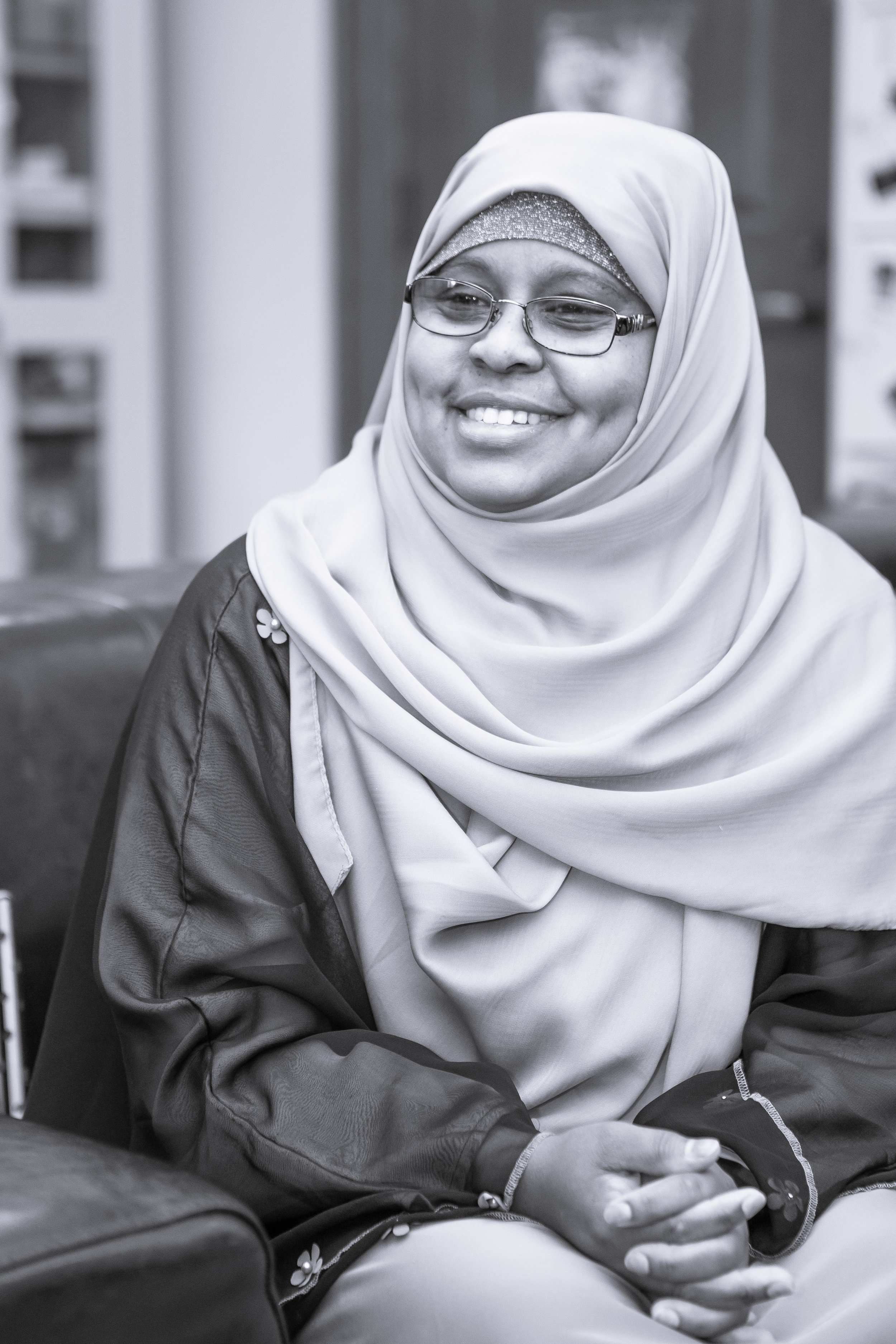

Ruqia Abdi: Reclaimer of Space

When Ruqia Abdi settled in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of south Minneapolis, her local library became a refuge. It was a space where she could peruse thought-provoking books, where her children could study undisturbed.

Still, Ruqia didn’t think that she truly belonged in the library. “Everyone was white except us,” she remembers. “I knew that I could use the library, and I did, but I didn’t feel like it was for me.”

Ruqia’s Somali neighbors seemed to share the same sentiment. Ruqia and her husband had moved from New Jersey — where they felt socially isolated and separated from their community — because they heard that “there is a place called Minnesota where you will find lots of Somali people,” she remembers.

However, Ruqia realized, you usually couldn’t find them in the library.

It wasn’t the first time that Ruqia, who came to the United States as a Somali refugee in 2000, felt disillusioned by her new home. Her first job as a Bilingual Education Assistant at Minneapolis Public Schools opened her eyes to the disappointing reality of the American education system.

“I had this idea of Western education, but what I saw was worse,” says Ruqia. “I thought, I’m in the United States of America, but what’s going on in the schools? I wanted my daughter to get the best education, so I pulled her out and started homeschooling.”

Ruqia had learned from her own mother that quality education can open doors for women. Many girls in Somalia lack equitable access to academics, according to Ruqia. Particularly for wives and mothers, educational opportunities are few and far between.

“When I was young I used to think that once you have children, your brain gets smaller,” Ruqia laughs.

Ruqia’s mother worked for the Somali government and wanted her children to learn English. Ruqia didn’t enjoy the extra lessons as a child, but now she says, “no one can stop me from continuing my education since I started learning from a young age.”

Now Ruqia teaches her three children that their schooling comes with considerable privilege — “I tell them that they have a blessing.”

That blessing was something that Ruqia wanted to spread and share with other children in her community. At the time that she pulled her oldest daughter out of public school, she was pursuing a medical degree, but she switched to child development. She was intent on becoming a professional educator, though not a classroom teacher “because then you’re confined to teaching 25 or 30 students.”

Ruqia yearned for a broader impact. An impact that would reverberate throughout her neighborhood, throughout the next generation of her community. With her characteristic spunk and her enthusiastic smile, she says, “I wanted to teach hundreds and thousands of children!”

That dream and determination is what brought Ruqia back to Hennepin County Library, the first place of learning that she discovered in her new neighborhood. Her volunteer supervisor Bernie Farrell, who now works as Youth Services Coordinator, was “the first individual who made me feel like the library could be for me too,” says Ruqia.

Bernie was also the person who motivated Ruqia to take advantage of a new opportunity. While volunteering, Ruqia was approached with an opening funded by the Minnesota Department of Education (MDE) through the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA). The library was looking for a Cultural Liaison, and with her wealth of community connections, Ruqia was an obvious choice.

In her new position, Ruqia led cultural competency training for staff at several libraries across Hennepin County. Library staff had many questions — for example, why would some community members leave their events early? “Most of us are Muslim, and we pray five times a day,” Ruqia would explain. “So if you host a gathering during one of those times, we’ll have to hurry out.” To address those considerations, the library changed the timing of certain events and created a prayer space in the facility.

Once the library system had embarked on these efforts to increase cross-cultural awareness and appreciation, Ruqia took charge of outreach efforts, introducing her rich network to library services. Together, she and her team developed a pop-up library featuring bookshelves, storytelling events, and children’s crafts.

“It was like a taste of the library coming directly to them, and they could ask any questions that they wanted,” says Ruqia. The goal of these pop-up events, hosted at community hubs such as schools, masjids, and apartment buildings, was to show community members how they can utilize the library — and to make the library a more welcoming space than Ruqia discovered as a recent immigrant. Always attentive to the children in her community, Ruqia especially encouraged parents and young families to attend.

To ensure that new library visitors discovered resources that would reflect their own lived experiences, Ruqia recommended cultural materials to purchase with funds from LSTA. These materials include the Quran, Seerah, Hadith, and Islamic stories for children as well as Arabic and Somali learning materials. Community members can request other materials, which the library usually purchases for the new collection.

After the year was up, Ruqia was hired as a part-time Associate Librarian, moving to full-time at Franklin Library about three months ago. Since this library is one that she supported through the grant project, Ruqia says that she is “new but not really new.”

And as a previous Cultural Liaison in the Hennepin County Library system, she remains a resource and continues to visit other locations. In addition to speaking Somali as a native language, Ruqia learned Arabic in school and knows verbal Urdu — allowing her to serve several South Asian communities situated across the county.

With her multilingual background and her familiarity with the education system, Ruqia has become a trusted resource for many members of these communities. “Whenever I am at the desk, people come because they know that I’m here. They want to know which school is best, what should they do if their child is slow in a certain subject…” she lists varied queries, many of which wouldn’t be expected in a library setting.

“Even when I go home, if they need anything, they come,” says Ruqia. “In my culture, if you don’t open the door, you’re rude. So if they receive a letter from insurance or economic assistance, for example, I have to translate.”

Language assistance and educational advice are only two of the areas of support that Ruqia offers. After years serving her community, Ruqia has become a prominent figure, a pillar of wisdom often solicited for advice — particularly by women. Their questions may begin with schooling and parenting, but sometimes they move into concerns around abuse or sexual assault.

After hearing repeated stories from survivors of violence in their homes or on the streets, Ruqia started seeing a pattern — “Women don’t get their voice heard. If they do try, they’re shamed, so they end up hiding.”

In order to fight against that paradigm of shaming and victim-blaming, Ruqia joined the Break the Silence movement, striving to end rape culture alongside survivors of sexual violence and allies. “We need to get rid of what’s not working,” she believes. “When we come to a Western country, we think that everything is fine, but no one is perfect in any society or any community.”

When a woman discloses a violent experience, “I try to listen as much as I can, and then I start giving them advice based on what I would do,” says Ruqia. The specifics of that advice vary depending on the situation, but it always comes with deep compassion.

Frequently Ruqia focuses on bringing survivors back into the community. “Since abusers use tactics to isolate them, I tell them to connect with friends and relatives, to invite those people into their lives,” she explains. Sometimes she offers to go out with them herself, bringing together her wide circle of friends for extra strength in numbers.

“Then I tell them that they need to study,” Ruqia says. Here, too, she holds firm faith in the power of education — “In this culture you can start from the ground up and get a GED. I tell them, you have a God-given right, it’s in the Quran — take action and get education.”

One woman who followed this advice recently graduated from St. Catherine University — and credits her educational success to Ruqia. Now that woman is pursuing a lucrative career that allows her new independence. “She always calls me and tells me what she’s going to do,” Ruqia says proudly. “It’s because she had support from me and other women.”

Ruqia won’t stop trusting women, advocating for survivors, and speaking out against systemic injustices. “I have girls,” she says steadfastly. “If I do not talk about this, it’s going to happen to them tomorrow. I have a boy. If I do not speak, he’s going to abuse his future partner, and I don’t want that to happen.”

After all, for Ruqia, it’s about the children. “There is a theory in child development that children grow in many contexts — family, community, greater society,” she explains. “All the time, I have this map in my head. And anyone who gets in the way of children, I’m going to be on top of them.” Ruqia flashes her customary smile with the last sentence, but there’s no doubt of her serious intent.

Ruqia’s vision for a world without violence — a world where educational equity and gender justice are realities — doesn’t waver. But sometimes, she needs a break from emotional labor and exposure to sensitive topics. She sets aside time for self-care, sharing that one of her secrets is to take Mondays off work.

“It’s so tough to do all these things,” she admits. “But all these things are a part of my life, so they don’t tire me out. I’m working on projects that are going to make people’s lives better, and I go home feeling like I did something good.”

And when she’s recharged and ready to return to work, Ruqia always loves making her way back to the library. Thanks to Ruqia’s uncanny ability to reclaim and reimagine places already familiar, Franklin Library has almost come alive today — its small space vibrant with visitors, many brown and black, many young. And not only does Ruqia find her friends and neighbors in the library today, but she also finds herself.

“It feels more homey now,” she says.